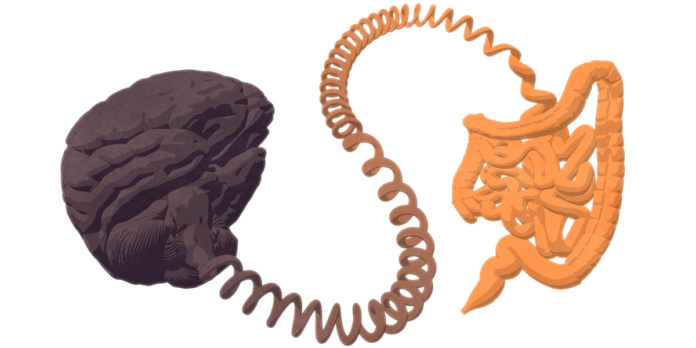

Researchers are discovering new connections between the brain and gut that could make a difference to the daily life of children with autism and their families.

A neuroscientist by trade, Dr Elisa Hill-Yardin never expected to find herself focused on the gut. But her pioneering research on the “gut brain” is helping us better understand its critical links with neurological disorders like autism and Parkinson’s disease.

It’s not just scientific challenge that drives her work – as the mother of a son with severe autism, Hill-Yardin’s passionate pursuit of discoveries in this emerging field has a personal edge.

The ARC Future Fellow and leader of the Gut-Brain Axis team in RMIT’s School of Health and Biomedical Sciences explains how the brain in our guts affects the brain in our heads.

What is the “gut brain”?

The enteric nervous system – or the gut brain – controls the contractions of the gut and its secretions.

It’s a big nervous system, about the same size as the spinal cord. Many of the same neurons that you find in the brain can also be found in the gut brain.

What are the links between the gut and autism?

An overwhelming majority of children with autism experience serious gut problems. It really impacts their daily life and behaviour and can stop them progressing with education and getting access to help.

Families have known this, but it’s only recently that research is catching up.

While we don’t know the cause of autism, we do know that there are hundreds and hundreds of rare gene mutations that alter brain connectivity.

The mutations affect synapses, which are like the “velcro” between neurons. Our team and others have been working to show that many of those mutated genes are also found in the gut.

In a sense that’s not surprising, as we know the gut has similar types of neurons to the brain, but people haven’t been looking there in the context of autism.

Do you think many “brain” diseases might have a gut component?

Absolutely. I think we are entering a new phase where researchers will be interested in changes in the nervous system as a whole, not just the brain itself.

There are a couple of reasons for this. First, many diseases report early onset symptoms in the gastrointestinal tract and inflammatory changes are also likely to happen here.

Secondly, the gut nervous system is a great region to work with because the outputs are relatively easy to measure – we can actually see gut contractions for example, whereas the brain doesn’t “flex” when we think.

What is your team’s specific focus in this field?

We’re looking at one particular gene mutation and aiming to get very deep into our understanding of that. The reason we do that is we think we’ll be able to uncover mechanisms that apply more broadly to those many rare genes.

The problem we have in the field is that there are so many rare genes but the advantage we have is that many of them share the same function and they’re found in the same location, at the interaction between neurons – the junction called the synapse.

Trying to learn more about autism by studying the immune system in the gut doesn’t seems like an obvious approach. Did you expect your research to take you in this direction?

It was so surprising because my background is in brain science and electrophysiology, understanding different types of neurons in the central nervous system.

So I came at this from a neuroscience perspective, looking to see what is changing in the gut nervous system. But what’s been amazing is when we alter only the nervous system, we then see changes in other systems, like the immune system.

It’s super exciting because it provides us a way to tweak the immune system, and researchers are very interested in exploring how our immune system relates to the severity of autism symptoms and outcomes. So we’ve got a really great tool there.

I get amazed all the time by our research. What holds us up – but is really exciting – is that every time we look at something and think we’ll just measure something basic, we find something new.

So even something as simple as measuring the length of the gut – lo and behold, this mutation in the nervous system might be changing that as well. This work, it’s full of surprises.

What do we still need to learn about gut microbes and their role in health and disease?

Simple answer – we need to know which ones are present, and how they change in response to different stimuli. We also need to know in what circumstances different types are detrimental or advantageous to the host.

One of the things that was completely surprising to me in this research was the role of the microbiota – that is, the trillions of bacteria that live in your gastrointestinal tract.

We’ve learned that the microbiota can differ even when you remove all the environmental differences. The fact our mice show differences in microbes even when they’re housed together, eat the same food; that just blew me out of the water.

I never expected it to be microbes, I thought that only the nervous system would be involved. We don’t quite understand the pathways, but we now know microbes play a far more important role than we ever believed. That link, it’s really astounding.

As you’ve gone down these pioneering paths to examine the gut-brain connection, what has it been like for you sharing this new knowledge with families and the community?

I’ve had a lot of support from families. Starting out in a new area like this, when the literature and the field is not that well established, it’s risky.

But going back and speaking to families, and also from my personal experience as a mother of a child with severe autism, that gave me more confidence that this really is an issue and we need to work on it and try to understand it.

I have the tools to do that as a neuroscientist, since that was my training before my children were born, so it’s really quite fortuitous.

I’m transferring what I know of the brain to this emerging field so all of that expertise has now essentially been harnessed in my focus now, the gut-brain axis.

(Source: RMIT University)